Coffee: A Cup of History

February 27, 2017By former ANCA-WR Intern: Nayiri Partamian

According to scholar Mark Pendergrast in Uncommon Grounds, a goatherd, Kaldi, discovered coffee in what is today Ethiopia, after his goats  strangely reacted to the consumption of a coffee berry. The coffee bean was first discovered much before Armenians, Greeks, Bulgarians, and Arabs got their hands on this warm, liquid form of coffee. Before the Early Modern Ages, the Khat coffee plant in Ethiopia was boiled and used for waking during prayers (Pendergrast, 2010). Coffee was then domesticated in Yemen fifty years later before reaching the Ottoman Empire and even the Early Modern Ages in Europe.

strangely reacted to the consumption of a coffee berry. The coffee bean was first discovered much before Armenians, Greeks, Bulgarians, and Arabs got their hands on this warm, liquid form of coffee. Before the Early Modern Ages, the Khat coffee plant in Ethiopia was boiled and used for waking during prayers (Pendergrast, 2010). Coffee was then domesticated in Yemen fifty years later before reaching the Ottoman Empire and even the Early Modern Ages in Europe.

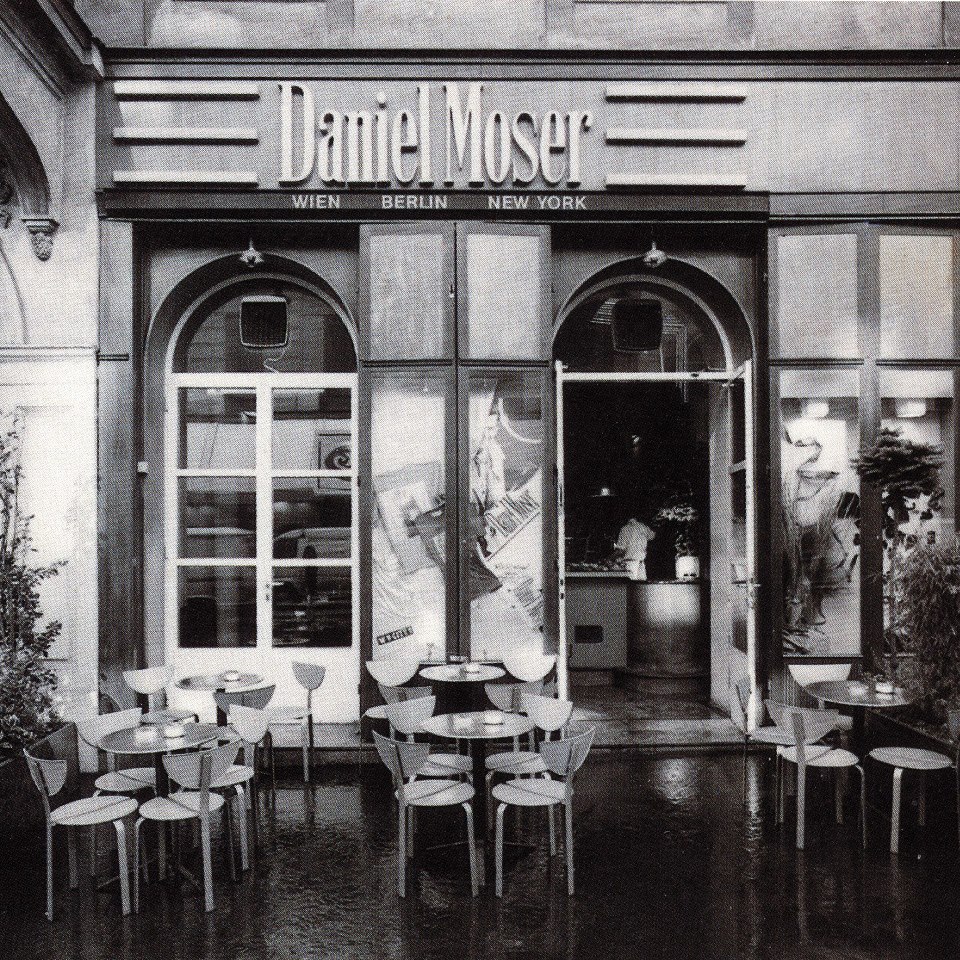

I had found myself in the right place, Vienna, Austria in the spring of 2015 when I was conducting my senior thesis on Armenian coffee traders in Europe. An Armenian man by the name of Hovhanness Diodato had opened the first coffee shop in Vienna, Café Daniel Moser, located in Vienna’s most crowded tourist zone, Schwedenplatz. Little could one tell this tiny, modern bar had existed for over hundreds of years. There is sparse amount of evidence of its historical existence aside from Diodato’s name engraved on the side of the bar on a small plaque. Vienna is already quite a modern town. Most of its buildings were rebuilt in the 20th century following World War II. Before Vienna became a more modernized megalopolis, the Ottomans had become a threat to certain European powers in the 16th century and as a result, the Viennese had fought alongside the Germans and Poles under King of Poland John III Sobieski against Ottoman Grand Vizier, Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha. The defeat by the European powers had destroyed the Ottoman dream of capturing Vienna as a strategic link between Western Europe and the Black Sea. This event was coined as the “Siege of Vienna,” fought between September 11 and 12 in 1683 as part of the Ottoman-Hapsburg wars, lasting for about 265 years. According to legends, this battle had led to Vienna’s first encounter with coffee, when an Ottoman soldier had left behind a bag of coffee beans at the battlefield after fleeing defeat. A polish man by the name of Mr. Kolschitzky had gathered the beans on site.

Mr. Diodato, born as Hovhanness Astvatsatour, meaning “God-Given,” opened the first coffee shop in Vienna in 1685 following Emperor Leopold I’s grand impression of the “pulverized” form of coffee made by his servants at home. The first coffee shops were opened by Armenians in Prague, Paris, Venice, and London as well. Café Procope, not to cause confusion with Café de Procope, was the first coffee shop in Paris opened by an Armenian man, Pascal. He had also opened the first coffee shops in London (1652), Venice and Holland. Prague’s first coffee shop, “Zlatého Hada” or “Golden Snake,” was opened by Deomatus Damajian, or Dajamanus. According to the owners today, in 1714 “the Armenian trader Deodatus Dajamanus sold coffee outside the building to passers-by; it was the first time that this exotic novelty was served in Prague.”

Armenians around the world are celebrating their history with coffee in Armenia as well. Pascal and Diodato Café owned by Pierre Baghdadian, is located in Ashtarak, Armenia. The owner asks, “Can you imagine Paris without its Cafés? Vienna without its coffee shops? But to let two strangers sit beside each other and have a ‘strange dark green liquid’ was an unbelievable innovation made by our fellow patriots, but never recognized by the world…not even by our people simply because Armenia was under The Ottoman Empire’s occupation for centuries and subject to Genocide and destruction of the people, which then led to a total loss of our nation’s history’s traces.”

Coffee was not just limited to Western Europe during the time, but has been embedded in the Armenian culture for a while as well. According to scholar Helen Makhdoumian, drinking coffee and having your cup read is an intimate time to escape from the oppression experienced from surrounding nations. According to Irina Petrosian and David Underwood (2006) of Armenian Food: Fact, Fiction & Folklore “a drinker should put his or her thumb into the grounds at the bottom of the cup, and press hard enough, this shows you are opening your heart for the fortune teller’s examination” (2006). Armenians did not encounter coffee until after the Early Modern Ages, but in the 19th century when Armenians were being oppressed, ‘coffee time’ was and still is a representation of the survival of culture (Makhoudiam, 2013), because this is where individuals, generation after generation, began to learn and listen to the untold stories of their ancestors. Coffee is in our history, whether it be the coffee traders and pioneers in Europe or the Armenian coffee drinkers right here in our homes.